It’s hard to become not something when you’ve been that something for a long time. It’s hard to break up with your first career. For the record, it wasn’t demography, it was me, and I hope someday we can be friends.

But for now, like the fallout after my first serious romantic relationship, I’m left wondering what went wrong and whether I can ever commit myself to something again. Can I say with conviction that I’m a something like I stated I was a demographer?

I’m not not a demographer now. I still know a lot about demography and am intrigued by demographic questions, but I’m not practicing. Thus, the label chafes a bit.

The process of redefining myself started months prior to my departure from academia. It was during the crying time that I began to search for something that I could become. I looked back to what made me happy before I started down the road to academia and pinpointed college as a time when I shut down my creative endeavors and lost touch with a fundamental part of myself.

Writing was the first way I reconnected. In the spring of 2012, I started attending one of Atlanta’s storytelling shows, Carapace. I wrote stories about my life and performed them. I shared my failures, my triumphs, my insecurities. I’d always seen the past as a fixed thing, but storytelling taught me that the past was much more fluid. I could choose how to tell my story. I’m choosing how to reveal it to you now. I’m empowered. I’m a storyteller. I’m a writer.

I’m an improviser. I asked for improv lessons for Christmas in 2012. I felt stupid putting it on my list, scared of revealing this desire to my family. Fear has held me back from a lot of things. In college, I would practice sometimes with Ohio Wesleyan’s improv troupe, the Babbling Bishops, but I was too afraid of rejection to audition to be a member. In my first improv class at Dad’s Garage, the instructor asked whether any of us hoped to perform improv on stage someday. I didn’t raise my hand because I didn’t want to admit I had that goal. I didn’t want to fail. Luckily, improv is a great way to learn to accept failure, celebrate it even. I failed, I learned.

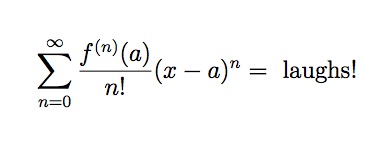

I perform with two improv troupes now: Shark Party and !mprov (pronounced Bangprov). I’m writing a mathematical romance novel. I’ve performed at many of Atlanta’s great live lit and storytelling events including Carapace, Naked City, Stories on the Square, The Iceberg, and Write Club Atlanta.

I’m an improvisor, a storyteller, a writer, but it’s difficult for me to define myself by activities that don’t pay. I’ve long judged art as an impractical pursuit while secretly wanting to be an artist.

After I started writing my novel last July, I would get depressed whenever I went to a bookstore. Shelves full of books that inspire wonder in my reader self spell doom in my writer self. There are already so many books! (And loads more that never got published.) Why would mine matter? What contribution could I possibly make?

I’ve always been more comfortable as a big fish in a small pond.

Approaching the problem from a demographic angle helped to quell my despair. Yes, book writing is a risky endeavor. The numerator, the number of people who are super successful, is small. The denominator, the number of people who pursue it, is large. I may never get published. I may never make money.

But there is something to be said for being part of the denominator even if I never make it into the numerator. Writing a book is hard – plugging away at it every day, trying to keep the story consistent, wondering if I will ever finish. So while shelves stocked full of books intimidate me, they also give me hope. If millions of people have chosen to do this despite the difficulty and succeeded,* then maybe I have made a good choice – not necessarily because my book will have a big impact but because it brings me joy. I’m part of the community of writers, storytellers, and improvisers who pursue these often monetarily unprofitable endeavors because they enjoy it and because they can entertain others by doing it.

I’m an improviser. I do this for myself. I do this to make people laugh and make people feel things, sometimes things that scare them.

I’m a storyteller. I do this for myself. I do this in hopes that sharing my burden lessens the weight others carry. I do this so we all fell less alone.

I’m a writer. I do this for myself. I do this because I think falling in love is one of the best things in life and romance novels allow the reader to experience these emotions vicariously. I do this because I think love and sexuality should be celebrated.

I’m an artist. I create things. I do this because it makes me happy.

*Google estimates from 2010 indicate close to 130 million books exist. Regarding my use of the word chosen, presumably a small number of authors did not choose to write books but were forced to. Some might take this footnote as evidence that I’m still a demographer. I probably am.